Dzieje stadionu (English)

Z Historia Wisły

| Linia 39: | Linia 39: | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| + | ==Second stadium 1922-53== | ||

| + | The main task of the authorities of TS Wisła after the reactivation of the club's activities in 1918 in the reborn and independent Republic of Poland was to obtain land from the city authorities for a new stadium. As "Sport lwowski" vividly depicted at that time: "As soon as the war subsided, old Wiślacy emerged as if from underground, returned to the workshop, and the power of their will, solidarity, the power of love for ideals and spirit of these people prevailed." However, before that happened, Wisła wandered around foreign fields during the first years of the Second Polish Republic. Wisła "explored various foreign corners, but it never even dreams of ceasing to exist, although others, luckier, are already in possession of their own territory. It's like a hungry stray dog showing its teeth to well-fed bandogs settled in beautiful houses. If the sight of its teeth doesn't evoke sufficient respect, it is always ready to try them on the opponent's skin, often with painful results. These are the sporting successes of Wisła. Victories over the possessors of beautiful fields, facilities, managed by experienced masters. In the country and abroad." The press wrote with admiration: "This team deserves even more admiration and respect because it doesn't have its own field in Kraków" (Ilustrowany Kurier Codzienny, August 9, 1919). It should be mentioned here that maintaining a club (football team) at a sufficiently high level without its own sports facilities was considered almost miraculous in those times. It was primarily associated with the costs of maintaining the team. There were no government or municipal subsidies supporting clubs at that time. On the contrary, municipalities (especially the city of Kraków) imposed high taxes on gross income from sports events (one could rather say extortion). These taxes were much higher than in other cities in Poland (reaching 40%). Therefore, clubs relied on ticket sales for matches, as the material and financial support from club members and "affluent" benefactors was not significant at that time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the normal functioning of the club, having its own stadium became a sine qua non condition for its continued existence. Clubs without their own sports facilities had to borrow them from wealthier neighbors (usually not without self-interest - the rental fees for using, for example, Cracovia's field cost Wisła an average of about 15% of gross ticket revenue or a significant lump sum). Wisła played its matches in Kraków on the fields of Cracovia and Makkabi. The costs of maintaining the club, therefore, increased proportionally, and the questionable profits from the organized matches often turned into losses. All it took was bad weather or fewer spectators than expected, and the club found itself in financial trouble. Another negative consequence of this situation was the small group of loyal fans forced to follow their team around to foreign places. Since the fans were the main benefactors of the club during this period, paying for tickets, it created a vicious cycle. For the normal existence of a club with tradition and ambitions like Wisła, having its own stadium and field became a necessary matter. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The construction and opening of its own stadium played a significant role, as evidenced by Wisła's results. With the establishment of solid material foundations in the form of its own sports facilities, the "Reds" became an equal rival to Cracovia and decisively surpassed them in the following years, competing for the highest laurels in the national championship. The efforts to acquire land for Wisła's field began in early 1919. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On March 29, 1919, during the first General Meeting of TS Wisła after World War I, a resolution was passed to jointly request the City Council, together with the Kraków Cycling and Motorcycle Club, to allocate land for the future stadium. This request was reiterated at the Annual General Assembly on November 14, 1919, as the previous one had no effect. The need for its own field is best demonstrated by a fragment of the meeting's protocol: "The General Meeting earnestly requests the new board to energetically pursue the acquisition of its own field from the municipality since other much younger societies already have their own fields, while 'Wisła,' one of the oldest sports societies in Poland, still does not possess one. The President assures that his and the board's aim will be to strive for obtaining their own field, and the meeting adjourns without further discussion." | ||

| + | |||

| + | After many efforts, Wisła managed to obtain the approval of the municipal authorities and began the construction of the stadium. Initially, our club wanted to buy a part of the land from the former racecourse, but the city authorities did not agree to it. Therefore, leasing was the only option. The modest financial resources of the Society meant that any selfless assistance was gratefully accepted. The players themselves participated in the construction of the facility, even sacrificing their per diems during Wisła's tour in Romania (September 1921). These funds were used to build a wooden fence around the stadium, and the "team personally leveled the received field." The presence of many professional soldiers in Wisła resulted in assistance from their side, as "the military provided 2000 meters of barbed wire for fencing and 100 kg of nails." The management of the entire facility was entrusted to Marian Kopeć. By the end of 1921, the work was progressing at full speed, but there was a lack of funds for further construction. The offer of money from the club's vice-president, Franciszek Wojas, did not solve the problem. It was decided to ask the members of the Society to pay their contributions in advance for 3 years, and institutions for financial or in-kind support (such as wood). For this purpose, an account was also opened at PKO Bank Polski. Fundraising events were also organized, with the proceeds going towards financing the construction. It was essential to complete the construction along with the start of the new football season. The covered grandstand was designed by the renowned architect Roman Bandurski. Wojas paid for it out of his own pocket, and the Society gradually tried to repay this debt. The covered grandstand, which was built, resembled a combination of a "Chinese pagoda with a Polish nobleman's manor," and it made a considerable impression on the fans even during the construction phase (the grandstand could accommodate 1,800 people, although the original plan was for a capacity of 2,500). It also impressed local journalists and editors of Kraków newspapers. It was noted, however, that the grandstand was "...beautiful but not very practical." The field was separated from the spectators by a track, and behind it was a 1-meter wooden fence. A refreshment stand was located in the wing of the grandstand and operated during the events. Underneath the grandstand, after many years, changing rooms with showers were built, which was a luxury in those times, and an earth mound was constructed for standing spectators opposite the grandstand. The cost of building the grandstand amounted to approximately 13 million Polish marks. The track itself was "considered excellent by experts." Unfortunately, initially it was not the case with the field. "Przegląd Sportowy" in 1922 wrote: "The field itself does not present itself in the best way and still requires significant investments(...)". The implementation of the investment was completed, with a significant contribution from Józef Szkolnikoswski, who is considered the initiator of the efforts to have their own Wisła corner. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The grand opening of the new sports stadium finally took place on April 8, 1922. "Finally" because the opening date of the Sports Park had been postponed twice (initially scheduled for March 12, 1922, and then March 25). The entire ceremony began at 9:30 am with a religious service at the Capuchin Church in the Loretan Chapel. The stadium was blessed by Father Anioł from the Capuchin Order, and the "official" opening of the field was performed by the president of the Polish Football Association, Dr. Cetnarowski, who cut the ribbon. For the inauguration, Wisła defeated Lviv's Pogoń 4-2. The stadium was on the corner of 3rd May Street and Miechowska Street (now Reyman Promenade). The stadium served Wisła for many years, being a silent witness to many memorable moments. For example, Marshal Józef Piłsudski visited it in 1924, one of the most exciting derby matches in the history of these encounters took place there (Wisła - Cracovia 5-5), and in 1926, the Polish Cup final was played there. Wisła's stadium was the first to have an Omega clock installed during the memorable championship season of 1927. It was located across from the wooden grandstand. Having one's own field, apart from the obvious benefits, also had its drawbacks. It required insurance payments and costly renovations. The repair of gutters and the roof of the grandstand financially strained the Society to such an extent that President Aleksander Dembiński was authorized to take out a loan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Disasters did not spare this facility either. On August 14, 1935, a storm that struck Kraków completely destroyed the grandstand. Only the remnants of broken planks served as a reminder of its existence. "Even the mighty concrete support pillars buckled under the onslaught of the raging storm," wrote the press. To rebuild the grandstand, Wisła took out a loan, which caused financial difficulties for the club until the outbreak of the war. The final renovation work was scheduled for August 1939, and the club requested the allocation of 10 workers from the Labor Fund for this purpose. The club, in fact, employed various methods to raise funds for the stadium's reconstruction. In October of that unfortunate year, during the Wisła-Makkabi boxing match, the competition was preceded by a "display of strength by Mr. Radwan. An extraordinary strong man, a Polish sailor, Mr. Radwan, effortlessly twists iron bars into spirals, breaks horseshoes, coins, drives thick nails into wood with his own hand, and so on. He will perform selflessly, dedicating any potential proceeds to the reconstruction of the Wisła Sports Club's grandstand." And so it happened. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The facility miraculously survived the turmoil of World War II, largely due to its continued use by a football team. Unfortunately, it was not Wisła. Poles were forbidden from engaging in organized sports, and many buildings, including Wisła's stadium, displayed a significant sign stating that only Germans were allowed to use it. In late October 1939, the facility on 3rd May Avenue was handed over to the German 3rd Landesschiitzenregiment (3rd National Shooters Regiment). It was not just a football pitch and a grandstand fenced off by a railing. Along with the buildings, a considerable amount of equipment, not only for football but also for other sections, fell into the hands of the occupiers. The Wisła Park Sports facility was taken over by the Deutsche Turn und Sport Gemeinschaft team. DTSG was the first German civilian sports club within the Kraków area. It was founded by Wilhelm Góra, a former player of Cracovia and a Silesian. This first German club had a group of loyal supporters, and perhaps the most famous among them was Oskar Schindler, a German businessman and member of the NSDAP, who, through his actions, saved over 1,000 Jews from certain death. Schindler, known for his willingness to spend money, provided financial support to DTSG. Therefore, the stadium buzzed with football life until the German soldiers withdrew from Kraków. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On January 28, 1945 (10 days after the liberation of Kraków), after the removal of the sign "Nur für Deutsche" (Only for Germans), the teams of Wisła and Cracovia ran onto the field of the White Star to play the first football match in free Kraków (the city was free, but the war was still ongoing). Both teams took to the field wearing their historic colors. The white and red colors of both Wisła and Cracovia moved thousands of fans in the stands. After a short speech, the choral singing soared over the city walls: "Poland has not yet perished..." Wisła emerged victorious with a 2-0 score. The war spared the stadium, but in 1946, another storm completely destroyed the stands once again. This happened a week before the celebrations of the club's 40th anniversary. The stands were successfully rebuilt, but on a smaller scale. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wisła continued using the facility for couple of years until it has been completely dismantled in mid-50s, when a new, much larger stadium has been built nearby during the stalinist period. | ||

[[Kategoria: English]] | [[Kategoria: English]] | ||

Wersja z dnia 16:07, 18 cze 2023

Lack of appropriate facilities is an obvious handicap in the functioning of any sports club. It's no wonder that shortly after forming the team, Wisła took on efforts to acquire a piece of land for the pitch and stadium. At the initial phase Wisła played in Jordan's Park (public playground at that time at the outskirts of Krakow) or on Błonia (vast meadow next to Jordan's Park). With the growing popularity of football and rapid development of the sport, these makeshift pitches became insufficient.

The first attempt at building own facilities concerned an ice rink. The idea was simple: income generated by the ice rink would be used to pay for its cost, with the surplus devoted to future creation of football stadium. The unfortunate part was that the winter of 1909 was very mild. As Wisła described it many years later: We have no luck with our own nest. We wandered around the corners of various "trash" places, and when moments came that seemed like finally fate was starting to smile upon us and the possibility of obtaining our own facilities was approaching, unexpected catastrophes cut off our existence. That's how it was in 1909 when leasing the ice rink brought us a huge shortfall because, due to an exceptionally mild winter in Krakow that year, we didn't open the skating track for a single day (then we had to spend years repaying a high loan we took).

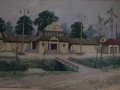

Oleandry Sports Park

Several years after the unlucky attempt at creating an ice rink, Wisła - now formally registered as a Sports Society - was granted another piece of land on lease. The efforts of - among others - president Marian Orzelski and board members Zdzisław Kiliński and Adam Obrubański were instrumental in this endeavour. Not far from the first unsuccessful investment, on the so called exhibition grounds (Exhibition of Architecture and Interiors in Garden Surroundings) in Oleandry, the first football facility of Wisła was built. A majority of members of the Wisła Sports Society were involved in the construction works, including the football players. The opening ceremony of the field took place on April 5, 1914. Wisła defeated Czarni from Lviv 3-2 in the inauguration of the new field. As reported by the Illustrated Sports Weekly, "The field itself, as well as the stands, do not look too impressive. The field still requires a lot of work to bring it to the proper value for football competitions. It is also not advantageous to have stands from which the entire field cannot be seen. More space should be left around the field because such narrowing hinders the game." (ITS, April 11, 1914)

Despite these inconveniences, after so many years, the stadium undoubtedly filled Wisła members and supporters with pride. It is also worth noting the rich facilities of the stadium, based on the remains of the Exhibition of Architecture, giving the Park Sportowy in Oleandry the character of a multi-functional facility. In a short time, various events were organized here, including festivities on the occasion of the May 3rd holiday, balloon flights, and art exhibitions. The park also had a theater hall and a concert shell. This made Oleandry have the potential to become an important place on the sports and cultural map of rapidly developing city of Kraków.

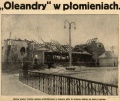

However, the players and fans enjoyed their own headquarters briefly. The outbreak of World War I thwarted the opportunity to expand the Oleandry Sports Park of Wisła. Józef Piłsudski's units were stationed in Oleandry with the club's authorities' permission. It was here that the First Cadre Company, the nucleus of the later Polish Legions, was formed. On August 6, 1914, the First Cadre Company marched off to the battlefield from here. When Piłsudski's Legions left Oleandry and Wisła suspended its activities, the stadium was taken over by the city of Kraków, which converted it into cow enclosures. A year later, in March 1915, due to oversight and negligence, the stadium was completely burned down. After the war, only ruins remained of the Oleandry Sports Park and Wisła had start everything from scratch.

Second stadium 1922-53

The main task of the authorities of TS Wisła after the reactivation of the club's activities in 1918 in the reborn and independent Republic of Poland was to obtain land from the city authorities for a new stadium. As "Sport lwowski" vividly depicted at that time: "As soon as the war subsided, old Wiślacy emerged as if from underground, returned to the workshop, and the power of their will, solidarity, the power of love for ideals and spirit of these people prevailed." However, before that happened, Wisła wandered around foreign fields during the first years of the Second Polish Republic. Wisła "explored various foreign corners, but it never even dreams of ceasing to exist, although others, luckier, are already in possession of their own territory. It's like a hungry stray dog showing its teeth to well-fed bandogs settled in beautiful houses. If the sight of its teeth doesn't evoke sufficient respect, it is always ready to try them on the opponent's skin, often with painful results. These are the sporting successes of Wisła. Victories over the possessors of beautiful fields, facilities, managed by experienced masters. In the country and abroad." The press wrote with admiration: "This team deserves even more admiration and respect because it doesn't have its own field in Kraków" (Ilustrowany Kurier Codzienny, August 9, 1919). It should be mentioned here that maintaining a club (football team) at a sufficiently high level without its own sports facilities was considered almost miraculous in those times. It was primarily associated with the costs of maintaining the team. There were no government or municipal subsidies supporting clubs at that time. On the contrary, municipalities (especially the city of Kraków) imposed high taxes on gross income from sports events (one could rather say extortion). These taxes were much higher than in other cities in Poland (reaching 40%). Therefore, clubs relied on ticket sales for matches, as the material and financial support from club members and "affluent" benefactors was not significant at that time.

For the normal functioning of the club, having its own stadium became a sine qua non condition for its continued existence. Clubs without their own sports facilities had to borrow them from wealthier neighbors (usually not without self-interest - the rental fees for using, for example, Cracovia's field cost Wisła an average of about 15% of gross ticket revenue or a significant lump sum). Wisła played its matches in Kraków on the fields of Cracovia and Makkabi. The costs of maintaining the club, therefore, increased proportionally, and the questionable profits from the organized matches often turned into losses. All it took was bad weather or fewer spectators than expected, and the club found itself in financial trouble. Another negative consequence of this situation was the small group of loyal fans forced to follow their team around to foreign places. Since the fans were the main benefactors of the club during this period, paying for tickets, it created a vicious cycle. For the normal existence of a club with tradition and ambitions like Wisła, having its own stadium and field became a necessary matter.

The construction and opening of its own stadium played a significant role, as evidenced by Wisła's results. With the establishment of solid material foundations in the form of its own sports facilities, the "Reds" became an equal rival to Cracovia and decisively surpassed them in the following years, competing for the highest laurels in the national championship. The efforts to acquire land for Wisła's field began in early 1919.

On March 29, 1919, during the first General Meeting of TS Wisła after World War I, a resolution was passed to jointly request the City Council, together with the Kraków Cycling and Motorcycle Club, to allocate land for the future stadium. This request was reiterated at the Annual General Assembly on November 14, 1919, as the previous one had no effect. The need for its own field is best demonstrated by a fragment of the meeting's protocol: "The General Meeting earnestly requests the new board to energetically pursue the acquisition of its own field from the municipality since other much younger societies already have their own fields, while 'Wisła,' one of the oldest sports societies in Poland, still does not possess one. The President assures that his and the board's aim will be to strive for obtaining their own field, and the meeting adjourns without further discussion."

After many efforts, Wisła managed to obtain the approval of the municipal authorities and began the construction of the stadium. Initially, our club wanted to buy a part of the land from the former racecourse, but the city authorities did not agree to it. Therefore, leasing was the only option. The modest financial resources of the Society meant that any selfless assistance was gratefully accepted. The players themselves participated in the construction of the facility, even sacrificing their per diems during Wisła's tour in Romania (September 1921). These funds were used to build a wooden fence around the stadium, and the "team personally leveled the received field." The presence of many professional soldiers in Wisła resulted in assistance from their side, as "the military provided 2000 meters of barbed wire for fencing and 100 kg of nails." The management of the entire facility was entrusted to Marian Kopeć. By the end of 1921, the work was progressing at full speed, but there was a lack of funds for further construction. The offer of money from the club's vice-president, Franciszek Wojas, did not solve the problem. It was decided to ask the members of the Society to pay their contributions in advance for 3 years, and institutions for financial or in-kind support (such as wood). For this purpose, an account was also opened at PKO Bank Polski. Fundraising events were also organized, with the proceeds going towards financing the construction. It was essential to complete the construction along with the start of the new football season. The covered grandstand was designed by the renowned architect Roman Bandurski. Wojas paid for it out of his own pocket, and the Society gradually tried to repay this debt. The covered grandstand, which was built, resembled a combination of a "Chinese pagoda with a Polish nobleman's manor," and it made a considerable impression on the fans even during the construction phase (the grandstand could accommodate 1,800 people, although the original plan was for a capacity of 2,500). It also impressed local journalists and editors of Kraków newspapers. It was noted, however, that the grandstand was "...beautiful but not very practical." The field was separated from the spectators by a track, and behind it was a 1-meter wooden fence. A refreshment stand was located in the wing of the grandstand and operated during the events. Underneath the grandstand, after many years, changing rooms with showers were built, which was a luxury in those times, and an earth mound was constructed for standing spectators opposite the grandstand. The cost of building the grandstand amounted to approximately 13 million Polish marks. The track itself was "considered excellent by experts." Unfortunately, initially it was not the case with the field. "Przegląd Sportowy" in 1922 wrote: "The field itself does not present itself in the best way and still requires significant investments(...)". The implementation of the investment was completed, with a significant contribution from Józef Szkolnikoswski, who is considered the initiator of the efforts to have their own Wisła corner.

The grand opening of the new sports stadium finally took place on April 8, 1922. "Finally" because the opening date of the Sports Park had been postponed twice (initially scheduled for March 12, 1922, and then March 25). The entire ceremony began at 9:30 am with a religious service at the Capuchin Church in the Loretan Chapel. The stadium was blessed by Father Anioł from the Capuchin Order, and the "official" opening of the field was performed by the president of the Polish Football Association, Dr. Cetnarowski, who cut the ribbon. For the inauguration, Wisła defeated Lviv's Pogoń 4-2. The stadium was on the corner of 3rd May Street and Miechowska Street (now Reyman Promenade). The stadium served Wisła for many years, being a silent witness to many memorable moments. For example, Marshal Józef Piłsudski visited it in 1924, one of the most exciting derby matches in the history of these encounters took place there (Wisła - Cracovia 5-5), and in 1926, the Polish Cup final was played there. Wisła's stadium was the first to have an Omega clock installed during the memorable championship season of 1927. It was located across from the wooden grandstand. Having one's own field, apart from the obvious benefits, also had its drawbacks. It required insurance payments and costly renovations. The repair of gutters and the roof of the grandstand financially strained the Society to such an extent that President Aleksander Dembiński was authorized to take out a loan.

Disasters did not spare this facility either. On August 14, 1935, a storm that struck Kraków completely destroyed the grandstand. Only the remnants of broken planks served as a reminder of its existence. "Even the mighty concrete support pillars buckled under the onslaught of the raging storm," wrote the press. To rebuild the grandstand, Wisła took out a loan, which caused financial difficulties for the club until the outbreak of the war. The final renovation work was scheduled for August 1939, and the club requested the allocation of 10 workers from the Labor Fund for this purpose. The club, in fact, employed various methods to raise funds for the stadium's reconstruction. In October of that unfortunate year, during the Wisła-Makkabi boxing match, the competition was preceded by a "display of strength by Mr. Radwan. An extraordinary strong man, a Polish sailor, Mr. Radwan, effortlessly twists iron bars into spirals, breaks horseshoes, coins, drives thick nails into wood with his own hand, and so on. He will perform selflessly, dedicating any potential proceeds to the reconstruction of the Wisła Sports Club's grandstand." And so it happened.

The facility miraculously survived the turmoil of World War II, largely due to its continued use by a football team. Unfortunately, it was not Wisła. Poles were forbidden from engaging in organized sports, and many buildings, including Wisła's stadium, displayed a significant sign stating that only Germans were allowed to use it. In late October 1939, the facility on 3rd May Avenue was handed over to the German 3rd Landesschiitzenregiment (3rd National Shooters Regiment). It was not just a football pitch and a grandstand fenced off by a railing. Along with the buildings, a considerable amount of equipment, not only for football but also for other sections, fell into the hands of the occupiers. The Wisła Park Sports facility was taken over by the Deutsche Turn und Sport Gemeinschaft team. DTSG was the first German civilian sports club within the Kraków area. It was founded by Wilhelm Góra, a former player of Cracovia and a Silesian. This first German club had a group of loyal supporters, and perhaps the most famous among them was Oskar Schindler, a German businessman and member of the NSDAP, who, through his actions, saved over 1,000 Jews from certain death. Schindler, known for his willingness to spend money, provided financial support to DTSG. Therefore, the stadium buzzed with football life until the German soldiers withdrew from Kraków.

On January 28, 1945 (10 days after the liberation of Kraków), after the removal of the sign "Nur für Deutsche" (Only for Germans), the teams of Wisła and Cracovia ran onto the field of the White Star to play the first football match in free Kraków (the city was free, but the war was still ongoing). Both teams took to the field wearing their historic colors. The white and red colors of both Wisła and Cracovia moved thousands of fans in the stands. After a short speech, the choral singing soared over the city walls: "Poland has not yet perished..." Wisła emerged victorious with a 2-0 score. The war spared the stadium, but in 1946, another storm completely destroyed the stands once again. This happened a week before the celebrations of the club's 40th anniversary. The stands were successfully rebuilt, but on a smaller scale.

Wisła continued using the facility for couple of years until it has been completely dismantled in mid-50s, when a new, much larger stadium has been built nearby during the stalinist period.